Holm’s essay extolls the virtues of Midwest prairies. Someone with a prairie eye, he writes, “looks at a square foot and sees a universe: ten or twenty flowers and grasses, heights, heads, colors, shades,” and more. The woods eyes, he writes—not better or worse, but different—looks for mystery and a sense of the baroque.

I didn’t care so much which landscape “eye” my students claimed. I cared only that they used their eyes and ears to see, hear, and be in whatever landscape they encountered. To facilitate perception, I took students out into local landscapes several times a year.

***********************

“We’re going to climb that?,” I overheard one student ask of another as we reached the base of a steep Mines of Spain hillside. To the left rose a sheer limestone wall, probably an old quarry not far from the river and just south of the ponds. To the right there was just enough foothold that by digging into the snow with our hiking sticks and grabbing onto tree trunks, we could pull ourselves up the incline. It may have been January Term, but after climbing the slope, we were plenty warm.

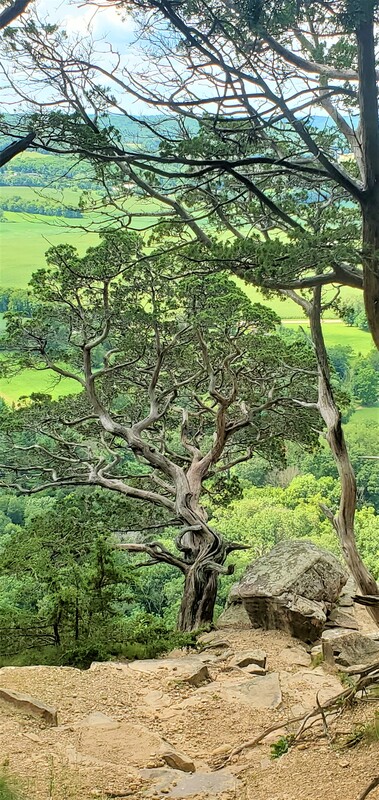

We were exercising our woods eyes. Here and there in the scraggly forest stood a few majestic burr oaks, 150-170 years old. Originally an oak savanna with a prairie carpet spread out beneath the scattered oaks, this river overlook would have been clear-cut for lead smelting furnaces in the 1800s, I explained, and the oldest oaks here today took root as lead mining came to an end. These old oaks took root in the relative absence of other trees and spread their limbs horizontal and wide. As the forest regrew, the younger trees had to stretch vertically for sunlight.

But the prize of this hike was located another hill over, down a ravine, and up another hearty climb. And there in the cover of woods and far from any summer-time trail, a simple hole dimpled the earth, then another as we curved up over the lip of the hill. And then another and another until we were in the lead-mine field, among hundreds of shallow pit mines dotting the river bluff like a crater-scape, each ranging in size from six to a dozen feet wide and four to eight feet deep.

I explained Dubuque’s lead-mining past as we zig-zagged among the pits. We playfully slid down into the larger ones and clawed our way back out. Spreading out across the woods, we searched for the widest and the deepest. After reaching the end of the mine field, we paused and looked out over the ice-caked river. I asked students to walk quietly back through the woods, imagining the miners who once roamed over this river bluff and who had tossed dirt, rock, and finally lead out of these holes.

The only other footprints in these woods besides our own belonged to deer and mice.

*******************

Alongside Catfish Creek at the Swiss Valley Nature Preserve, we tested our prairie eyes and talked about the stream restoration project completed several years earlier that had transformed the creek’s steep-walled, muddy banks into the gentle, grassy gradients that prevailed in pre-settlement times. Before the advent of quick, massive drainage associated with modern agriculture and municipalities, prairie grasses would have sidled down to the creek-side on slopes more ambling than precipitous. Occasional high waters could glide across the creek’s grassy twists and curves instead of further downcutting into the mud walls.

Sloping down from the tree line, last year’s dried prairie stubble poked through the sagging January snow as the students and I huffed upward to the hanging marsh. Located on an embankment halfway up the hill, the marsh is fed by small springs that flow practically year-round. Groundwater filters down from the crown of the bluff through the porous limestone, then

travels vertically on a layer of shale until it emerges in rivulets on the embankment. Warmer than the surface soil in winter, the springs encourage early season wildflowers while everything around it lies frozen. The constantly wet soil keeps the trees at bay, producing a marshy opening in the woods and boosting the warming power of the sun.

I encouraged my students to find where the spring waters emerge. Above, they noticed, there is frozen ground; below, a soil soaked and spongy.

**********************

In May Term and Fall, we drove to the base of Lock & Dam #11 on the Wisconsin side to exercise our river eyes. Far from a natural environment here, we talked about what the wandering river might have looked like before its harnessing. We considered the environmental impact of dams creating a narrower but deeper river and how barge engines churn up the river bottom. But we also discussed the economic benefits of barges, especially their relative fuel efficiency in comparison to rail and truck transportation of goods.

We watched the river roil and boil as it exited the gates on the downstream side of the dam, and noted the smooth upper pool surface stretching lake-like as far as the eye could see.

I told students about the habitat restoration above the dam at Sunfish Lake that protects fish breeding grounds from the swift flow of the river. Students were surprised to learn that they were standing on the shore of the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge (now celebrating its 100-year anniversary) that lines the river for 261 miles from Wabasha, MN, to Rock Island, IL.

*************************

After each outing I asked students to write about what they’d learned, but also what they’d reflected on or seen without my pointing it out. “I think I have a woods eye,” one student wrote, noticing the sun trickling down through the canopy. “But maybe I could have a prairie eye when the wildflowers are in bloom.”

Which eye she possessed wasn’t really the point. What mattered was that she had opened her eyes.

-- June 2024