The Loess [pronounced “luss”] Hills stretch in a thin band for 200 miles east of the Missouri River from Sioux City, Iowa, to northwest Missouri. Its 200-foot tall spine-ridged hills formed during the last ice age as powerful winds swept fine particles of glacial outwash, or loess, into the air and dropped them east of the Missouri River in ridges like gigantic snowdrifts. The formation, covering 650,000 acres, is found in such quantity in only one other location on earth, in China.

My wife Dianne and I, and friends Dana and Graciela, hiked some of the ten miles of trails at the 1300-acre Hitchcock Nature Center in the heat of a recent July afternoon. Our hike included the Badger Ridge Trail, which arcs up and down what is called a “razor ridge,” a narrow grassland spine from which the land dips suddenly away in both directions.

The loess ridges rise and fall like camel humps before us, offering sweeping views of distant farmlands, restored prairies, and woodlands of western Iowa. Wildflowers such as the Wood Germander poked out from the prairie in the heat of the day. The thinning of trees has allowed savanna wildflowers and prairie grasses like Silky Wild Rye to return naturally, without reseeding, after a long dormancy beneath the forest canopy.

The sweeping vista and wildflowers exist courtesy of the unique loess soil. A pinch of the fine, yellow-tan dirt exposed on the trail feel like a fine, brown flour between my fingers and thumb, and wafts quickly away in the breeze when released.

The loess soils are both stable and fragile. Left alone and prairie-covered, the hills are resistant to erosion. But when disturbed by development or overrun by forest, erosion can be quick and devastating.

Restoring the prairie is integral to preserving the loess landscape. Graeve, a 1996 Biological Research graduate of Dubuque’s Loras College, explains that Native Americans) routinely burned the prairies, which discouraged forest creep, herded elk and bison to new grazing grounds, and gave the burnt prairie time to recover. “Euro-Americans suppressed fires and kicked out the roaming elk and bison,” says Graeve, and as a result, forests have overtaken where prairie once flourished. Since prairie soaks up rainfall so well, water now runs off the landscape. Graeve adds, “When you deprive a system of water and sunlight, the system collapses.”

Through selective tree-cutting and aggressive annual fall prescribed burns, the prairie at the Hitchcock Nature Center is slowly returning to health.

The Hitchcock grounds might well have gone the way of much of the developed Loess Hills, however. From the 1960’s to 80’s the land served as a YMCA camp that introduced the city youth of nearby Omaha and Council Bluffs to nature, but then was sold to a private developer who intended to fill the steep valleys with refuse shipped in by train from New Jersey.

The developer began bulldozing some paths through the valley, whose scars are still visible today. The bulldozed paths created erosional runoff noticeable to nearby landowners, and a conservation movement arose to stop the landfill project and protect the hills. The landowner eventually defaulted on the property, allowing Pottawattamie County to make the initial purchase of land in 1991. Graeve says the Center hopes to eventually expand the grounds and reintroduce bison where possible.

For Graeve, though, preservation of the Hitchcock grounds is simply one part of the process of leading people back into “right relationship” with the land. “The real challenge,” he says, “is that we live in a society that is inconsistent with how the natural world works, and we have a broken relationship with the land.”

Indeed, Graeve dislikes the word “nature,” a term that creates a mental divide between our everyday experience and the non-human world. “People are related to the rocks, the birds, and the streams. If we can’t overcome that disconnect, we’ll always view the land as subservient to us,” he explains.

Graeve extolls a higher purpose as well. Few of us, he says, “link our food and water to the land, and ultimately to the Creator. We need to recognize our dependence on the land, and its dependence on us [for preservation]. Our relationship to the land needs to be one of respect, not dominion.”

Facilities and programming at the Hitchcock Nature Center are designed to “help people overcome their fear of the natural world and to come into right relationship with the land,” says Graeve. Backcountry hike-in campsites for tents and hammocks spur off from the trails over moderate to challenging terrain. Programming includes summer camps for kids and Owl Prowls and Snowshoe Hikes for all ages.

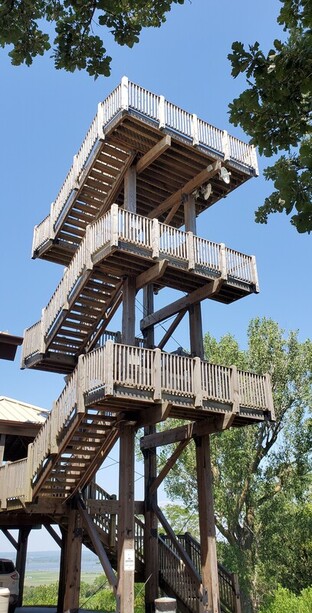

A 45-foot observation tower adjoins the interpretive center for viewing Iowa’s first Important Bird Area (IBA). Hawks are particularly plentiful as they inventory the prairie for rodents and other small morsels.

Graeve sees some, if slow, progress in Loess Hills preservation. In the past few decades, western Iowa counties have enacted zoning laws to protect the hills from rampant development, he says, and there has been some increase in public ownership. Additionally, conservation awareness of private owners has increased, “which shows that we’ve moved the needle a little bit.” That said, “We still haven’t come to value this landform for its intrinsic value,” says Graeve.

The Hitchcock Nature Center is a small corner of the Loess Hills, itself a thin, though globally significant, landform stretching along one American river. But preserving and restoring this one place, Graeve feels, is one step in bringing people back into right relationship with the land.

-- July 2019